5280 MAGAZINE

"Disassembly as an Act of Creation"

Charles Wooldridge

Below is the English interpretation of an article written by Jan Kriz Ph.D., art historian and critic, is a president of Czech division of International Association of Art Critics AICA.

*(The actual article is seen below the interpretation)

The idea of sculpture which can be separated into pieces or manipulated is part of the development of modern sculpture and it has been used by many of the world’s sculptors. It is a principle which has many shapes but which always counts on active participation of the perceiver or even co-creation of the actual shape of the piece. We move gradually from assembly and disassembly to participation on the action of the shapes. We are choosing various new configurations or speculate about uniqueness of individual pieces of the arrangement. This principle is well illustrated by the name of one of Wooldridge’s sculptures: To Cause To

Happen. This ”happening” of the sculpture is in its own space of perception and active experience.

The principle of manipulative sculpture is appearing in Czech art spontaneously, not just in geometrical sculpture where it seems that there are constructional reasons but also in area of figural metaphor, as is confirmed by work of Czech sculptors Radoslav Kratina and Karel Pauzer just to name marginal cases.

That’s why the work of Charles Wooldridge born 1961 in Denver, Colorado attracts our attention. He is the one who has achieved outstanding results in this area. Wooldridge is creating sculptures which can be taken apart into independent pieces. In the process of disassembly of the original whole structure there are not only many new shapes created but also free floating pieces that can be positioned in space and possibly perceived as independent three-dimensional formations.

It is the artist’s responsibility to keep the same level of originality, strength of expression, and identity with the starting formation in all stages of disassembly and in possible new combinations. This work, of course, requires extraordinary constructive imagination, especially if there are independent, expressive or lyrical shapes involved.

The individual parts must be smooth and secure at the same time so that in sliding them out and back in, the action itself can be enjoyable and pleasant. With Wooldridge, everything is perfect.

There is a certain amount of morality in it. The whole piece represents the coherence of the world, perhaps even the social coherence which quarantines protection provided by the mother port to the anarchic dissipation of the whole, the quarantee of the higher spiritual identity.

American sculpture has had a very good experience with decentralized or even anarchistic syntax. Perhaps that is one of the main contributions of American art – to explore the borders of freedom with acts of defiance and provocation, not as much as protest but more as positive acts as well as in decorative or expressive levels.

Woodridge can continue in this tradition. Reminders of abstract expressionism are mixing here with playful impertinence of Californian grotesque. But something new appears here – the desire to unite free imagination with solid organization and order. Here, America is getting closer to a European way of thinking, to synthesis, but it is letting both principles act in parallel. The conjunction of base construction created from steel and inside parts from warm white painted maple wood is understood in this sense. In these sculptures, the world of nature is reflected, tectonics of both body and crystals. Ultimately, we discover that something from the metaphor of surrealism echoes here. The individual pieces have very strong impressions of combinations of dramatic expression and dreamy lyricism.

Also, Charles Wooldridge works on bigger projects partially made out of fiberglass that are also open to manipulation by one person. For those who are less wealthy, there are playful desk top size sculptures, as I was reminded by my colleague, who introduced me to the artist, and who had one on his desk. This visit of the studio in the older part of Denver was a real experience.

Jan Kriz Ph.D., art historian and critic, is a president of Czech division of International Association of Art Critics AICA.

Charles Wooldridge

Below is the English interpretation of an article written by Jan Kriz Ph.D., art historian and critic, is a president of Czech division of International Association of Art Critics AICA.

*(The actual article is seen below the interpretation)

The idea of sculpture which can be separated into pieces or manipulated is part of the development of modern sculpture and it has been used by many of the world’s sculptors. It is a principle which has many shapes but which always counts on active participation of the perceiver or even co-creation of the actual shape of the piece. We move gradually from assembly and disassembly to participation on the action of the shapes. We are choosing various new configurations or speculate about uniqueness of individual pieces of the arrangement. This principle is well illustrated by the name of one of Wooldridge’s sculptures: To Cause To

Happen. This ”happening” of the sculpture is in its own space of perception and active experience.

The principle of manipulative sculpture is appearing in Czech art spontaneously, not just in geometrical sculpture where it seems that there are constructional reasons but also in area of figural metaphor, as is confirmed by work of Czech sculptors Radoslav Kratina and Karel Pauzer just to name marginal cases.

That’s why the work of Charles Wooldridge born 1961 in Denver, Colorado attracts our attention. He is the one who has achieved outstanding results in this area. Wooldridge is creating sculptures which can be taken apart into independent pieces. In the process of disassembly of the original whole structure there are not only many new shapes created but also free floating pieces that can be positioned in space and possibly perceived as independent three-dimensional formations.

It is the artist’s responsibility to keep the same level of originality, strength of expression, and identity with the starting formation in all stages of disassembly and in possible new combinations. This work, of course, requires extraordinary constructive imagination, especially if there are independent, expressive or lyrical shapes involved.

The individual parts must be smooth and secure at the same time so that in sliding them out and back in, the action itself can be enjoyable and pleasant. With Wooldridge, everything is perfect.

There is a certain amount of morality in it. The whole piece represents the coherence of the world, perhaps even the social coherence which quarantines protection provided by the mother port to the anarchic dissipation of the whole, the quarantee of the higher spiritual identity.

American sculpture has had a very good experience with decentralized or even anarchistic syntax. Perhaps that is one of the main contributions of American art – to explore the borders of freedom with acts of defiance and provocation, not as much as protest but more as positive acts as well as in decorative or expressive levels.

Woodridge can continue in this tradition. Reminders of abstract expressionism are mixing here with playful impertinence of Californian grotesque. But something new appears here – the desire to unite free imagination with solid organization and order. Here, America is getting closer to a European way of thinking, to synthesis, but it is letting both principles act in parallel. The conjunction of base construction created from steel and inside parts from warm white painted maple wood is understood in this sense. In these sculptures, the world of nature is reflected, tectonics of both body and crystals. Ultimately, we discover that something from the metaphor of surrealism echoes here. The individual pieces have very strong impressions of combinations of dramatic expression and dreamy lyricism.

Also, Charles Wooldridge works on bigger projects partially made out of fiberglass that are also open to manipulation by one person. For those who are less wealthy, there are playful desk top size sculptures, as I was reminded by my colleague, who introduced me to the artist, and who had one on his desk. This visit of the studio in the older part of Denver was a real experience.

Jan Kriz Ph.D., art historian and critic, is a president of Czech division of International Association of Art Critics AICA.

WESTWORD MAGAZINE

August 2003 (Winning the Colorado Open)

August 2003 (Winning the Colorado Open)

THE PASTEL JOURNAL

September/October 2000

Below is and article published by the pastel journal dedicated to the inventive qualities of my chalk pastels.

September/October 2000

Below is and article published by the pastel journal dedicated to the inventive qualities of my chalk pastels.

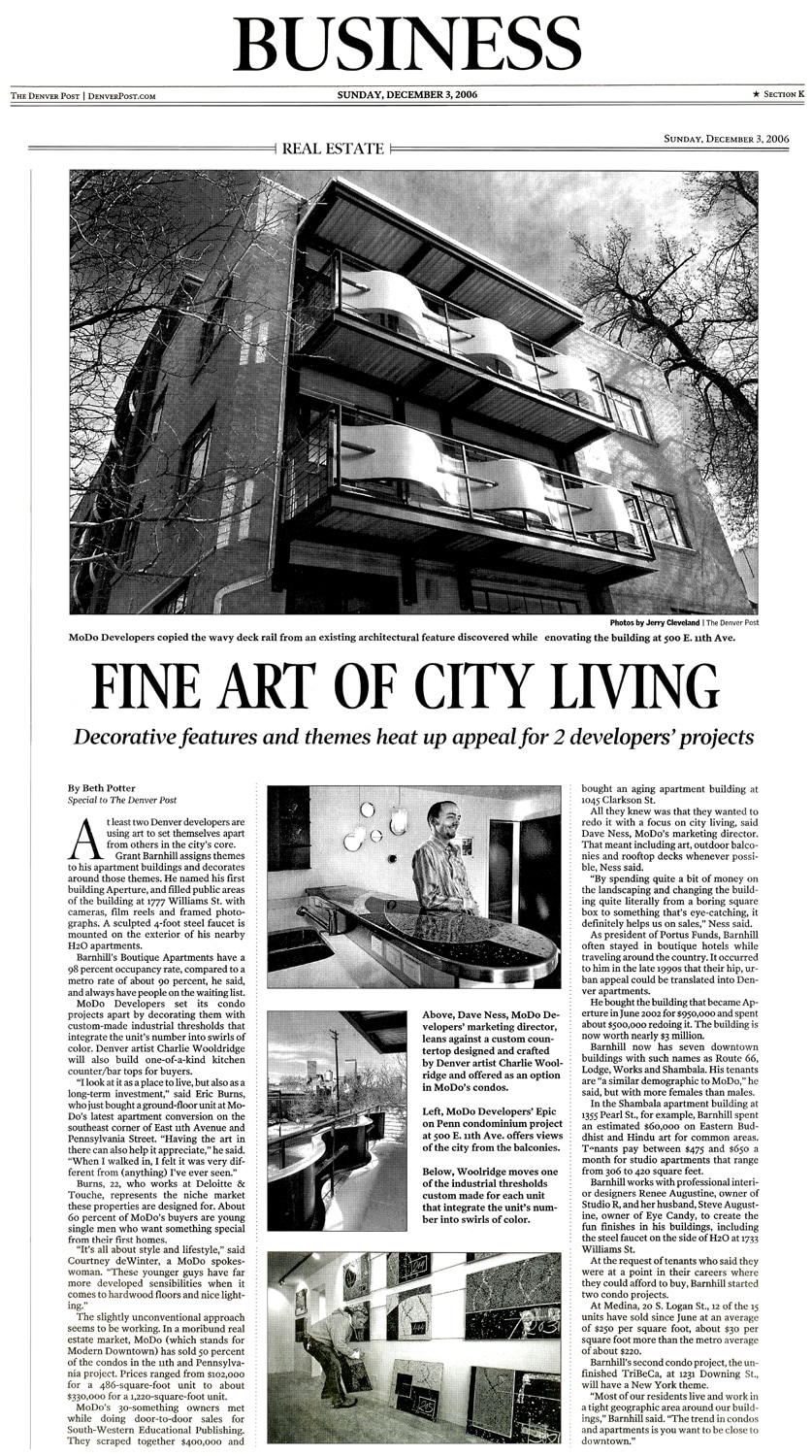

FINE ART OF CITY LIVING

The Denver Post, December 3, 2006

ART HOUSE

Rocky Mountain News, January 22,2005

Rocky Mountain News, January 22,2005

HOSPICE MASK PROJECT

Rocky Mountain News, May 11, 2006

BELOW is a link to the article that speaks of the sculpture seen directly below.

http://www.denverpost.com/2010/05/03/rsvp-generosity-heats-up-mask-project-gala/

Interior designer Mickey Ackerman started The Mask Project as a benefit for The Denver Hospice, and was elated to hear from chaircouples David and Bonnie Mandarich and John and Nancy Sevo that net income for the 2010 edition may top $650,000. A big chunk of that — $92,000 — is the result of donations sent in by friends of Steve Chotin to purchase “Lifting The Weight,” a mask he commissioned from Denver artist Charles Wooldridge. Chotin wanted to contribution a solid $95,000, so he put a dinner for 10 at Del Frisco’s up for bid and got the $3,000 he was seeking from Richard Rizzo of the new event planning company Puttin’ on the Rizz.

http://www.denverpost.com/2010/05/03/rsvp-generosity-heats-up-mask-project-gala/

Interior designer Mickey Ackerman started The Mask Project as a benefit for The Denver Hospice, and was elated to hear from chaircouples David and Bonnie Mandarich and John and Nancy Sevo that net income for the 2010 edition may top $650,000. A big chunk of that — $92,000 — is the result of donations sent in by friends of Steve Chotin to purchase “Lifting The Weight,” a mask he commissioned from Denver artist Charles Wooldridge. Chotin wanted to contribution a solid $95,000, so he put a dinner for 10 at Del Frisco’s up for bid and got the $3,000 he was seeking from Richard Rizzo of the new event planning company Puttin’ on the Rizz.

ARTFULY RESTORING THE SETLERS CABIN

Colorado Homes& Lifestyles April 1994